The University of Portsmouth have conducted a new study that has uncovered a dramatic collapse in traditional meadowland across the lower Rother catchment in South Devon, West Sussex, with losses of up to 99.9% since the mid-19th century.

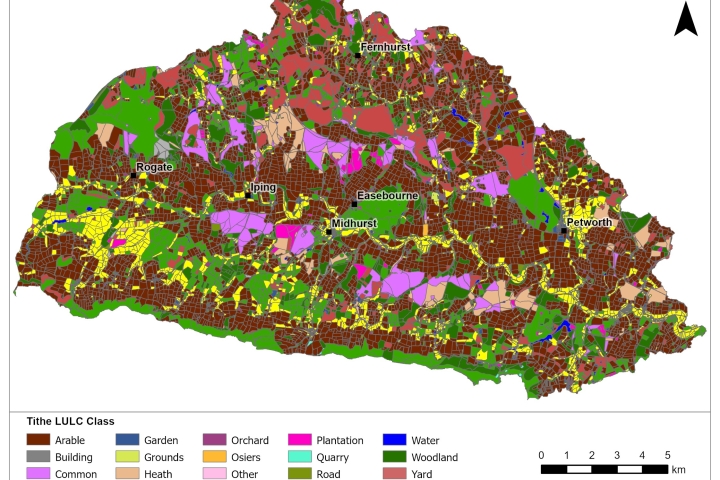

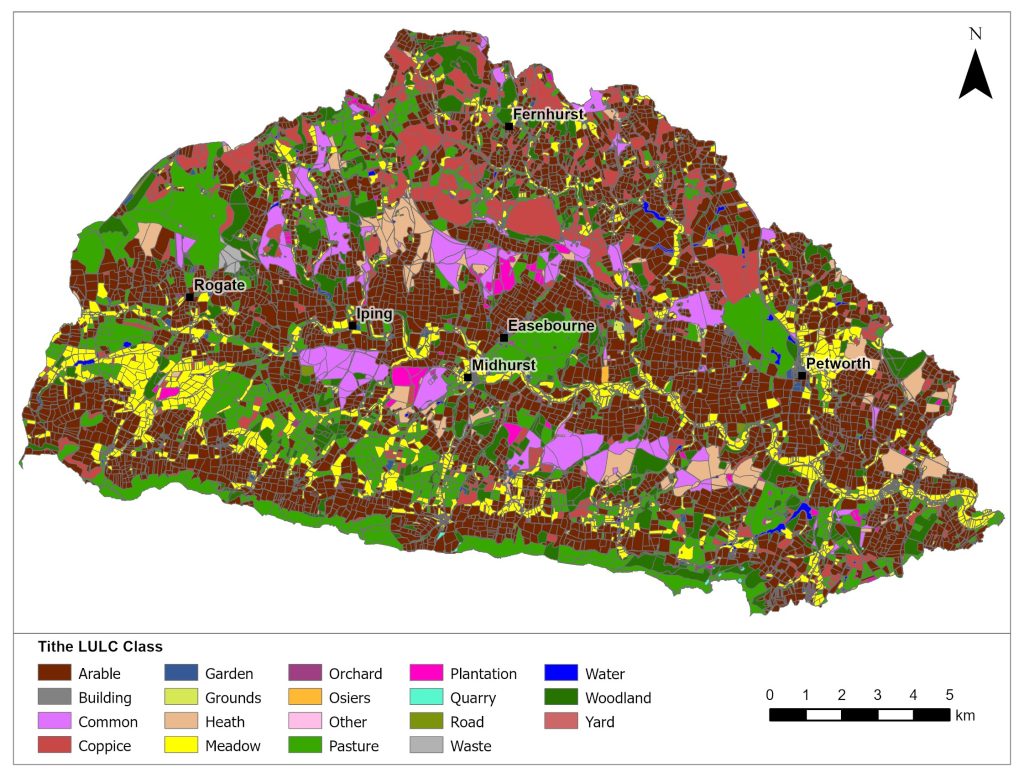

Using digitised Victorian tithe maps of the catchment, researchers compared historical records from around 1840 with modern land cover data from 2021. The results reveal how shifts in farming practices, land ownership and environmental policy have transformed the English countryside.

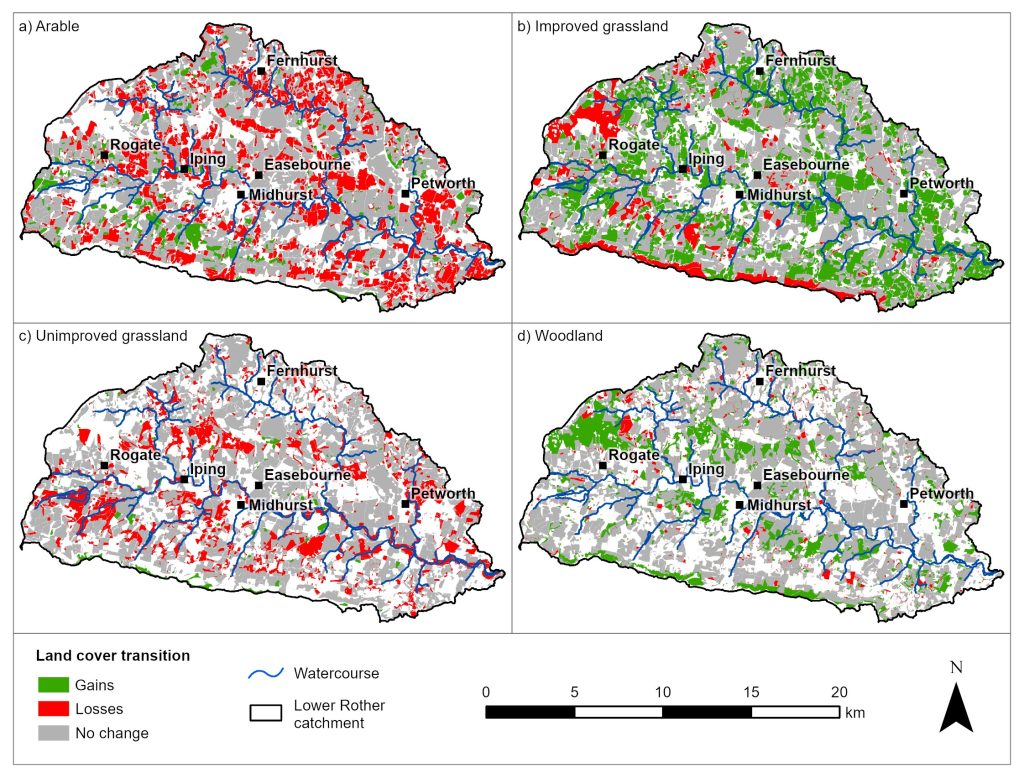

The study found that:

- Meadows have declined by between 75.6 per cent and 99.9 per cent, representing the greatest loss of any land cover type.

- Unimproved grassland, once rich in biodiversity, has fallen by 86.5 per cent.

- Arable land has reduced by 45.5 per cent, while improved grassland has increased by 135.8 per cent.

- Woodland has expanded by 56.3 per cent.

- Although the total area of common land has barely changed (down 1.7 per cent), its use has shifted from shared grazing to largely recreational woodland.

Dr Cat Hudson, from the School of Environment and Life Sciences at the University of Portsmouth, said: “Our findings show just how much the English countryside has changed since the 1840s. Meadows, once vital for haymaking, grazing and wildlife, have almost vanished. Understanding this transformation is essential if we want to restore biodiversity and build more sustainable landscapes.”

The team’s analysis demonstrates the practices that have gradually reshaped farmland since the Industrial Revolution, and turned once-common communal meadows and pastures into private, more intensively managed fields. These practices include agricultural intensification, enclosure and later government subsidy schemes, and although this process improved productivity, it did reduce habitat diversity and increased risks of soil erosion, biodiversity loss, and water quality degradation, which remain pressing issues for land managers and policymakers.

Dr Hudson added: “The landscapes we see today are the product of centuries of adaptation. But the historical record shows that past changes often came at the cost of natural resilience. Using tithe maps helps us understand how to balance productivity, conservation, and heritage in the face of climate change.”

This research highlights the importance of long-term evidence in shaping sustainable land management policies, and by using this historical landscape data, such as tithe maps and early land use records, policymakers can better target environment interventions to address modern challenges like soil degradation, carbon loss, and habitat fragmentation.

Dr Harold Lovell, from the School of Environment and Life Sciences at the University of Portsmouth, said: “Historical records offer a powerful tool for identifying where restoration could have the greatest impact. By recognising the cultural and environmental significance of features like meadows, hedgerows and field boundaries, we can encourage interventions that protect both the landscape’s heritage and its future ecological health.”

It is now recommended that policymakers use historical landscape evidence to inform targeted agri-environmental interventions, ensuring that efforts to improve soil health, carbon storage, and biodiversity also respect and restore traditional landscape features.

These findings support the UK Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan, which calls for the restoration of semi-natural grasslands, conservation of ancient woodland, and protection of rural heritage features such as hedgerows and field boundaries. They also provide an evidence base to guide local land management within the South Downs National Park and beyond, helping authorities like Natural England and the South Downs National Park Authority to deliver policies that integrate cultural heritage with modern environmental goals.

“By linking the past to the present, we can make better decisions about the future of our countryside,” added Dr Harold Lovell. “Historical evidence like this can guide us toward farming systems that are productive, resilient, and rooted in the landscapes that shaped them.”

Figure 1: the extent of meadows from the historical tithe dataset.

Figure 2: the locations of unimproved grassland gains and losses across the catchment; meadows are included as part of the grassland type.