Rediscovering long forgotten music does not mean recovering how it was meant to be performed, and that is a major challenge for the arts, finds a new study from the University of Surrey. An expert found that rediscovered music comes with no shared understanding for how it should sound, leaving performers to make radically different interpretive choices that reshape the work itself.

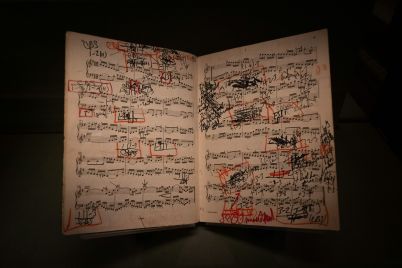

In an article published in Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, a researcher focused on a little-known piano miniature by Surrey-based British composer Ethel Smyth, written in the late nineteenth century and forgotten for 120 years. When the piece re-emerged in the 1990s and began to be performed again, no traditions of interpretation had survived. There were no clear instructions for tempo, expression or dynamics, and no recordings of historical performances to learn from.

To understand what happens when performers face this problem, the research compared all professional recordings of the same rediscovered work. Using specialist audio analysis software, each performance was measured beat by beat to track tempo and rhythmic fluctuation across the piece.

Each pianist approached the music in a fundamentally different way, particularly at its unfinished ending. Some slowed dramatically, others pushed forward and none aligned closely with one another. Even the earliest modern recording failed to establish a shared interpretive reference point.

Dr Christopher Wiley, author of the study and Head of Music and Media at the University of Surrey, said:

“When musicians open a score like this, they are standing on empty ground. While written in standard notation that is commonly understood, there is no inherited wisdom to lean on as to how the piece is supposed to be played. What I found when analysing modern recordings was not small variation in interpretation but completely different musical identities emerging from the same notes. This is creative and exciting, but also unsettling.”

The research argues that this challenge will only grow, as more pieces by historically marginalised composers are rediscovered. Nor is it an issue unique to music: performers across arts disciplines such as theatre and dance will likewise increasingly encounter works stripped of their original interpretive traditions.

Rather than relying solely on manuscripts, the study proposes more imaginative solutions: performers may need to draw on unconventional sources such as letters, memoirs and personal writings to guide interpretation. In this case, Smyth’s later autobiographical descriptions of the person she aimed to portray through her music offered valuable insight into its character, mood and emotional intent.