When a long-forgotten piece of music is rediscovered, it is often treated as a form of recovery. However, new research from the University of Surrey suggests that while the notes of a piece may survive, the original sound of the work can never be replicated.

In a study published in Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, Dr Christopher Wiley, Head of Music and Media at the University of Surrey, explores what happens when a musical score re-emerges without any surviving performance tradition to guide it.

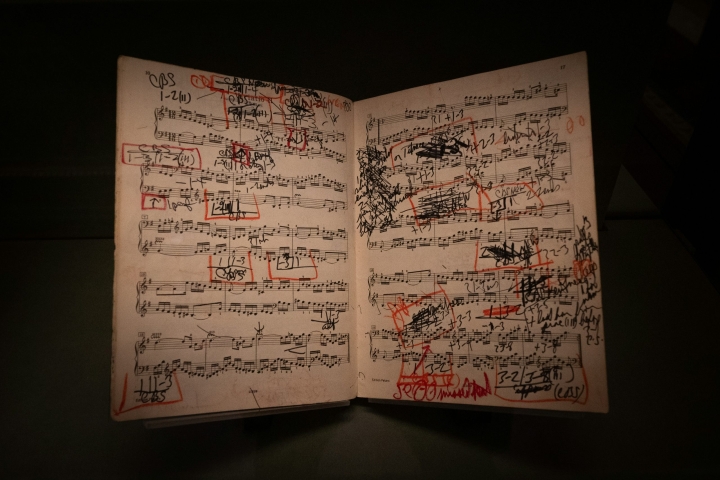

The focus of the research is a little-known piano miniature by the Surrey-based British composer Ethel Smyth. Written in the late nineteenth century, the piece disappeared for 120 years before resurfacing in the 1990s. At its renaissance, musicians were confronted with a problem: the score existed but the interpretive knowledge that once shaped how it was played had vanished. There were no historical recordings, no established tempo markings beyond basic notation and no inherited conventions of phrasing or dynamics passed down through generations. The written page offered structure, but little guidance as to character, pacing or expressive intent.

To explore how performers responded to this absence, the study analysed every professional recording of the rediscovered piece. Using specialist audio software, each interpretation was measured beat by beat to track tempo choices and rhythmic characterisation across the work.

What emerged was not minor variation, but striking divergence.

Pianists made fundamentally different decisions, particularly at the piece’s unfinished ending. Some slowed the tempo dramatically, giving the conclusion a reflective weight; others moved forward with momentum. No single version established itself as an interpretive reference point – not even the earliest modern recording.

Dr Wiley comments:

“When musicians open a score like this, they are standing on empty ground. While written in standard notation that is commonly understood, there is no inherited wisdom to lean on as to how the piece is supposed to be played. What I found when analysing modern recordings was not small variation in interpretation but completely different musical identities emerging from the same notes. This is creative and exciting, but also unsettling.”

The research highlights a wider issue facing the arts. As increasing attention is paid to rediscovering works by historically marginalised composers, performers are more frequently encountering pieces which have lost their interpretive lineage. The score may have been preserved in an archive, but the living tradition – the accumulated understanding of how it should sound – has not.

This creates a tension between revival and reinvention. Without access to the composer’s intended interpretive style, each performance risks reshaping the work in ways that move further from its original context.

The study suggests that performers seeking greater authenticity may need to look beyond the manuscript itself. Letters, memoirs and personal writings can offer valuable clues. In Smyth’s case, her later autobiographical reflections on the individual she sought to portray through her music provide insight – material that may help bridge the gap left by missing performance traditions.

Even so, complete recovery remains out of reach.

Once the original interpretive culture surrounding a piece has faded, what returns is not a fixed artefact but a set of possibilities. A sound reconstructed, inevitably, by performers today.